Mathematics in Art

Author: Utcarsh Mathur

BSc.

Mathematics (Hons.)

One of the biggest misconceptions prevailing in society is that Mathematics is just about numbers, equations and complex formulae. However, Mathematics encompasses much more than these. Mathematics is a discipline connected to many others and cannot be studied in isolation. Historically, Mathematics has been intimately related to art. Many mathematicians have, in fact, called Mathematics an art itself.

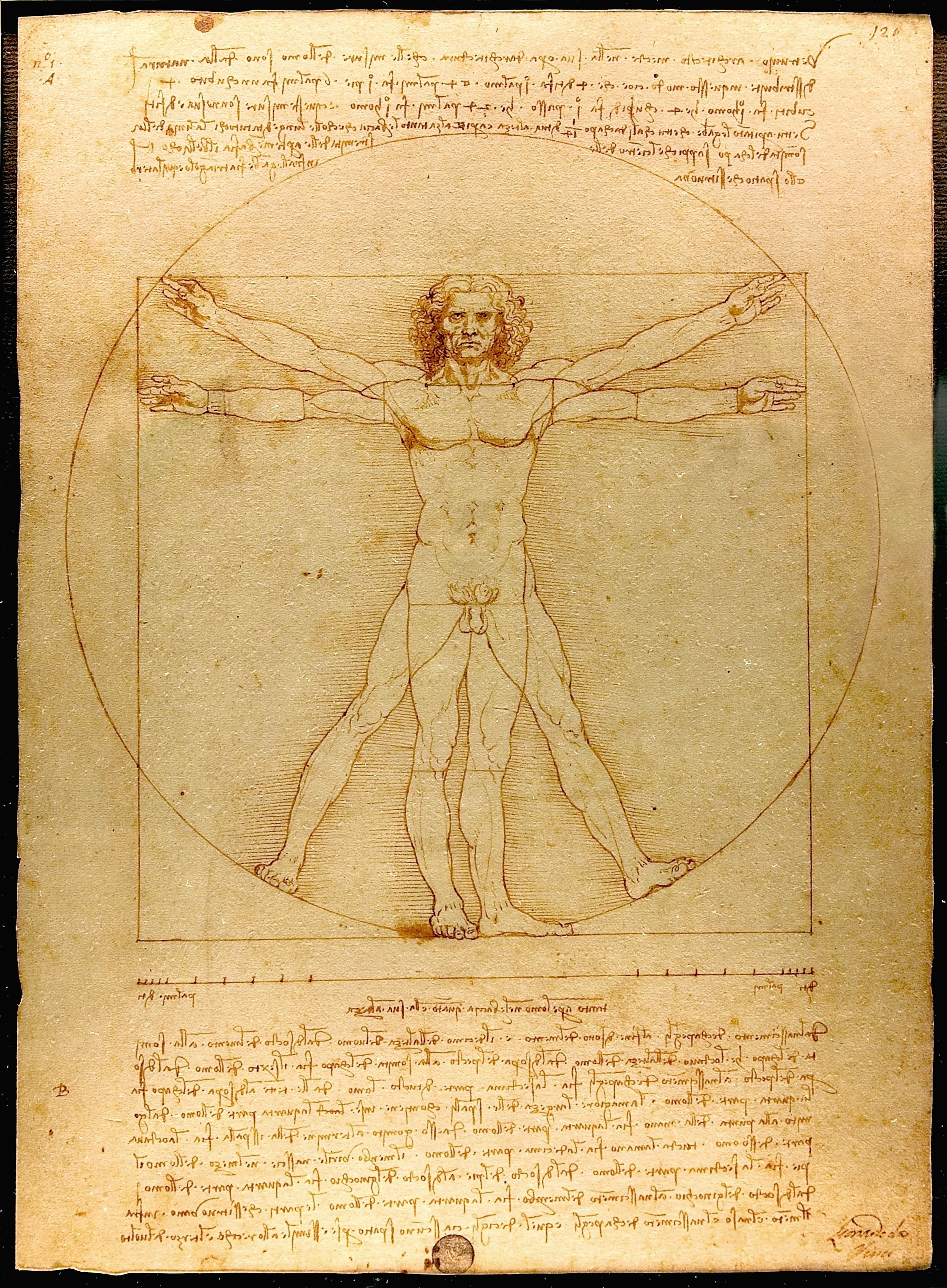

The relationship between Mathematics and Art bloomed from the 15th century onwards, during the Renaissance Period, particularly during the High Renaissance. Works of artists focused on what came to be known as “Realism”, that sought to depict the world as is; with its perfection as well as its fallacies. An intricate knowledge of geometry, ratio and proportion also aided the artists. In fact, the concept of a ‘Renaissance Man’ came into being; a person with multiple talents and knowledge in multiple disciplines. Works of artists such as Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) and Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) depict the same. One particular work of art, The Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci, highlights how Mathematics and Art were intertwined.

Also called “The Proportions of the Human Body according to Vitruvius”, the Vitruvian Man is a 15th century drawing that is accompanied with notes (written in mirror writing) that depict the ideas of Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, as described in Book III of his treatise De Architectura. Rendered in pen, ink and metal point on paper, the drawing depicts a man standing within a circle and a square. It shows the man with his legs vertical and arms horizontal superimposed on the image of him with arms and legs stretched out. It may be noticed by examining the drawing that the combination of arm and leg positions creates sixteen different poses.

Squaring a Circle

The Vitruvian Man is believed to be Leonardo’s attempt to solve the ancient greek geometric problem of Squaring a Circle. The challenge is to construct a square and a circle of equal area using only a compass and a straightedge. It has been proved, however, that it is impossible to solve this problem due to the transcendental nature of Pi. Vitruvius believed that the naval was the center of the human body that could be inscribed in a circle with arms and legs stretched out. He also believed that the armspan was equal to the height of the human and thus could place the body perfectly inside a square. Leonardo used the ideas of Vitruvius to metaphorically solve the problem by depicting mankind to fit the square and the circle. He thus uses the human body as a possible solution.

Perfect Proportions

-

Leonardo also depicts ideal body proportions in the drawing. He has drawn the Vitruvian Man with

utmost dexterity. The accompanying notes explain the same:

- four fingers equal one palm

- four palms equal one foot

- six palms make one cubit

- four cubits equal a man’s height

- four cubits equal one pace

- 24 palms equal one man

-

Further, in the second block of notes in the drawing, da Vinci discusses “15 proportional rules” for

drawing the human body that may be summarized as follows:

- The length of the outspread arms is equal to the height of a man

- From the hairline to the bottom of the chin is 1/10th of the height of a man

- From below the chin to the top of the head is 1/8th of the height of a man

- From above the chest to the top of the head is 1/6th of the height of a man and so on

Leonardo’s collaboration with Luca Pacioli, the author of Divina proportione (Divine Proportion) have led some to speculate that he incorporated the golden ratio in Vitruvian Man, but this is not supported by any of Leonardo’s writings, and its proportions do not match the golden ratio precisely. The Vitruvian man is likely to have been drawn before Leonardo met Pacioli. Leonardo, through the Vitruvian Man, sought to depict the perfection of nature manifested in the form of a human being. Both him and Vitruvius believed that just like the human being was perfect and proportionate, so should architecture be. Many architects such as Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) also applied the ideals of proportion but forth by Leonardo and Vitruvius in his works.

The Vitruvian Man has many layers of meaning. Many believe that da Vinci was trying to depict the Neoplatonic idea of ‘The Great Chain of Being’. This idea is prevalent in many religions. It follows that the world is hierarchically divided into a chain consisting of different elements of the Earth, and mankind is placed right in the middle of this chain.

Conclusion

Mathematics is a dynamic discipline that can be seen everywhere. Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, in his Il Saggiatore wrote that “[The universe] is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometric figures.” Besides the Vitruvian Man, artworks such as The Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, also by da Vinci have a mathematical dimension to it. Mathematics can likewise be seen in architecture, for example, in the Notre Dame, Paris, the Great Mosque of Kairouan, the Parthenon and so on, which are said to be demonstrated by the golden ratio. Mathematics has roused textile arts, such as quilting, knitting, cross-stitch, crochet, weaving etc, Turkish and other rug making, as well as kilim. In Islamic craftsmanship, symmetries are obvious in structures as varied as the Persian girih and Moroccan zellige tilework, Mughal jali punctured stone screens, and across the board muqarnas vaulting.

The mathematician Jerry P. King describes mathematics as an art, stating that “the keys to mathematics are beauty and elegance and not dullness and technicality”, and that beauty is the motivating force for mathematical research. The beauty of Mathematics is in fact, enhanced when incorporated with other disciplines, especially art.

- Wiki. The Vitruvian Man \

- Article. The Elegant Mathematics of the Vitruvian Man

- Article. The Significance of Da Vinci's Vitruvian Man

- A Human Body Mathematical Model Biometric Using Golden Ratio: Evon Abu-Taieh, Hamed S. Al-Bdour

- Human Modeling in Information Technology Multimedia Using Human Biometrics Found in Golden Ratio, Vitruvian Man: Evon Abu-Taieh, Minwer El-Maheed, El-Maheed, Alia Abu-Tayeh, Jeihan Abu Tayeh, Abdullah El-Haj

Figure 14.1

Figure 14.2